(In Search of) The Perfect Lecture is a performative lecture that traces the physical and conceptual boundaries of the lecture theatre in relation to modes of communication, performance and pedagogy.

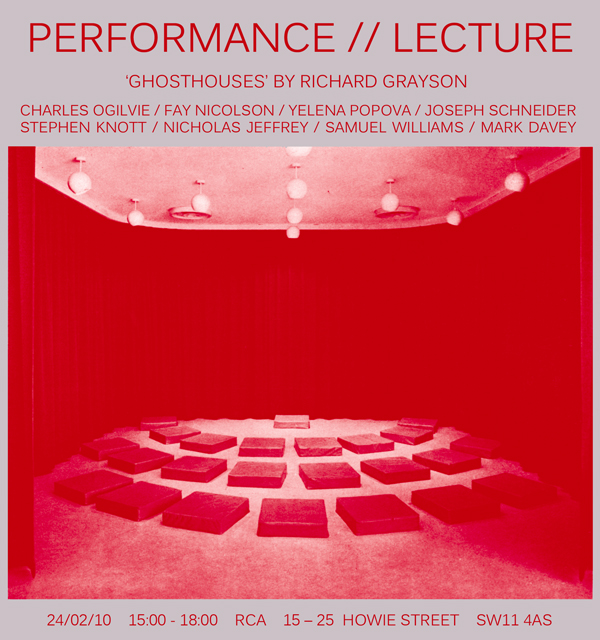

It was written for and delivered at an event called Lecture performance at the RCA organised with fellow artist, Charles Ogilvie. (For more information about this event please see the press release below).

Fay Nicolson

Join RCA staff, students and guests for an afternoon of performance lectures in the Seminar Room, Painting from 15:00 on 24 February. Artist, writer and curator Richard Grayson will be delivering his lecture ‘Ghosthouses’ at 15:30 followed by a short break and a series of student pieces from 16:30.

The lecture is an elusive formality. Defining relationships, structures and spaces it attempts to establish boundaries between audience, speaker and subject that may reinforce robust narratives, encourage new meaning and histories, spark loose associations or disintegrate in the chaos of mis-communication. Where is the lecture’s place in academic and creative practice and what are its possibilities as a model of communication and performance?

The genre of the performance lecture could be seen as taking inspiration from practices of live art, institutional critique and critical pedagogy. Through the form of the lecture creative professionals often challenge notions of authorship, the academy and traditional models of knowledge transferral. For this event a selection of artists will deliver a diverse series of performance lectures, adopting an array of experimental, academic and performative approaches. There will also be opportunity for discussion about the event and wider related issues over refreshments.

Richard Grayson – ‘Ghosthouses’

Bio: Richard Grayson is an artist, curator and writer. Recent solo exhibitions include a retrospective of his work over the last five years at the De La Warr Pavilion Bexhill 2010 and the video installation Golden Space City of God at Matts Gallery London 2009. He was a founder member of the Basement Group in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, 1979-84, director of the Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide Australia 1992 – 1997,

and curator of the 2002 Sydney Biennale (The World May be) Fantastic. He has written numerous articles and catalogue essays and is a contributor to Broadsheet Australia and Art Monthly UK.

Samuel Williams – ‘The Natural World’

A short film based on the Pecha Kucha model of presentation.

Nicholas Jeffrey – ‘Abandonment in the car head flux’

The piece will evolve loosely; from Marion’s idea of the super abundance within painting, the excessive in art, and is influenced by William Burroughs and Brion Gysin’s cut up techniques.

Stephen Knott – ‘Being an amateur’

Is there anything to learn from amateurs? Can concepts of amateurism help understand wider conditions of wider artistic production? This presentation is based on theoretical and historical research on the concept and will attempt to present the subject in a novel fashion.

Fay Nicolson – ‘(In Search of) The Perfect Lecture’

As an artist, writer and teacher Fay traces the physical and conceptual boundaries of the lecture theatre in relation to modes of communication, performance and pedagogy.

Charles Ogilvie – ‘Rational Myth’

From his body of work exploring the relationship between Cosmology and Mysticism, Charles presents the ambiguous legacy of Greek philosopher Pythagoras.

Yelena Popova – ‘Nuclear Guinea Pigs’

Yelena Popova will give an account of Cold War nuclear rash.

Joseph Schneider – ‘DUMBSTRUCK’

Something of a chant. Disconnected words that spill out like a fountain. A song about Samuel Spectacular. And other phantom tableaux.

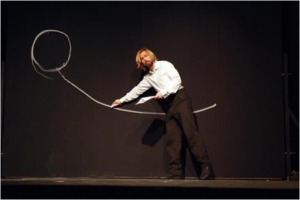

Mark Davey – ‘Put a Ring on It’

Mark Williams works towards animating the otherwise dull and stationary components of everyday life to make them extraordinary. Using lights as physical components, he makes them seductively, erotically, perversely kiss and touch; by moving, by swinging or rubbing themselves over other materials. The sculptures promise a breaking or failure that never quite arrives.

Notes for:

(In search of) The Perfect Lecture 1

1. OPENING A LECTURE 2

Avoid a ‘cold start’. Minimize nervousness. Grab student’s attention with your opening. Open with a provocative question 3, startling statement 4, unusual analogy 5, striking example 6, personal anecdote 7, dramatic contrast 8, powerful quote 9, short questionnaire 10, demonstration 11, or mention of a recent news event 12. This is advice given about strategies for effective lecturing from the book ‘Tools for Teaching’ by Barbara Gross Davis. 13

2. INTRO – What makes a good lecture? 14

As an artist who is also a student and a teacher, I have been thinking quite a lot about lectures recently, and the spaces that they occupy. In terms of space, I mean the architectural space that contains and conditions a discourse. I also mean the wider contextual space of the lecture within models such as the college, university or museum, or the space in which meaning and narrative form, whether through a monologue or a multi-directional conversation. 15

3. LECTURE THEATRES: A Typology 16

I find lecture theatres fascinating spaces.

Every time I enter one I get drawn into examining the space: its shape and scale, its age and decor, its carpet, lighting, the handrails.

In a way, a room such as this is caught between wanting to be invisible (designed in order to provide the optimum visual and audio experience) and wanting to somehow signify the values of the institution that houses it (how important is this lecture theatre in relation to the function of the wider institution, and what does this institution think about academia, the transferral of knowledge and public assembly?)

This lecture theatre built in 1902 is at the North of England Institute of mining and mechanical engineers and was built to the same design as the lecture theatre of the Royal Society in London. 17

I would love to go on a tour of lecture spaces, to see and document them. Perhaps the collected images would take the form of a book, or a lecture itself. In enlightenment fashion I imagine attempting to categorize them; those constructed before 1900, those which are central to the building, those which encourage you to talk rather than listen. 18

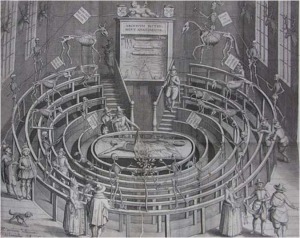

I could extend this collection to other spaces that were built for public assembly with a central focus. From lecture theatres I find myself situated in an operating theatre. 19

The operating theatre is a site of science, anatomy, surgery, but also of spectacle, voyeurism and mortality. 20

This engraving shows the anatomical lecture theatre at the University of Leiden, from Johannes Van Meurs’ Portraits, Elegies and Lives of the Professors of Leiden, 1617. Two men examine an open corpse on the dissecting table. The Latin inscriptions on the flags read (left) ‘The beginning of death is birth’ and (right) ‘Death renders equal the sceptre and the hoe’. 21

From operating theatre to amphitheatre 22 – the ancient Roman amphitheatre was a large central performance space surrounded by ascending seating, and was commonly used for spectator sports. From the transmission of knowledge we reach an engagement with entertainment. 23

Or the contemporary stadium – such as Old Trafford; a site of mass gathering. 24

I could move onto explore the space of the theatre (which is perhaps a return to space similar to the lecture theatre); a site for performance and recital. 25 A place you could go for entertainment and escapism, where you may suspend your disbelief, or not if you were to go and see some Brecht. 26

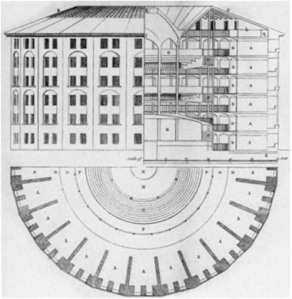

And yet, all of these centrally organised viewing systems remind me of the Panopticon 27, a design invoked by Foucault in Discipline and Punish 1975:

‘The principle is simple: On the periphery runs a building in the shape of a ring: in the centre of a ring stands a tower pierced by large windows that face the inside wall of the ring; the outer building is divided into cells, each of which crosses the whole thickness of the building. These cells have two windows: one corresponding to the tower’s window; facing into the cell; and the other, facing outside, thereby enabling light to traverse the entire cell. One then only needs to place a guard in the central tower, and to lock into each cell a mad, sick or condemned person, a worker or a pupil’. Foucault in conversation with Jean-Pierre Barou.

And here is Bentham, the social reformer and inventor of the Panopticon concept in 1785:

‘Morals reformed— health preserved — industry invigorated — instruction diffused — public burthens lightened — Economy seated, as it were, upon a rock — the gordian knot of the poor-law not cut, but untied — all by a simple idea in Architecture!’ 28

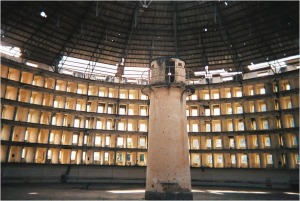

And here is the Prisidio Modelo, (Model prison), Cuba, built between 1926 – 31.

4. SPECTATOR / AGENT: Reading 29

Within these different spaces of public congregation, spectacle and mass dissemination I am interested in the definitions of the different people party to these events; in the definition of ‘Lecturer’ as not only a reader but also as actor (in terms of his performance but also in terms of him being the active agent in a process of meaning production). I am also interested in the potential definition of the audience as viewer, listener, spectator, interpreter, contributor, or if we follow Barthes line of thinking, the author.

‘The reader is the space on which all the quotations that make up a writing are inscribed without any of them being lost; a text’s unity lies not in its origin but in its destination.’

Roland Barthes, ‘The Death of the Author’ in ‘Image Music Text’, 1977. 30

Like Bentham’s Panopticon, Guiseppe Penone’s performance ‘To Turn One’s Eyes Inside Out’ 1970, (in which he wears mirrored contact lenses) also reverses that theatrical relationship of the central figure as performer or subject. 31

This is an image of a lecture at a medieval university (from the1350s). The lecturer reads a text from his lectern, which is intern inscribed by the members of the audience, the scholars. Here, a lecture is a way of perpetuating a particular body of knowledge, almost like copying a document. 32

I like William Hogarth’s 1736 engraving, ‘Scholars at a Lecture’. Here the participants seem to take on an equal role, with the ‘audience’ having as much to say as the lecturer himself. 33

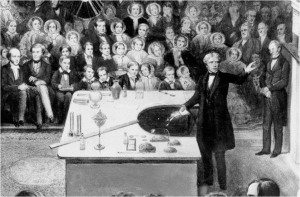

This is a detail of a lithograph of Michael Faraday delivering a Christmas lecture at the Royal Institution in 1856. Here we have the lecturer as demonstrator, alchemist or magician. And in this case the audience are a fairly ‘well to do’ and well behaved bunch. 34

And what about the relationship between the lecturer and audience outside of the physical Institution? 35 I think of Speaker’s Corner 36, which has in the past been frequented by the likes of Karl Marx, George Orwell and William Morris. 37

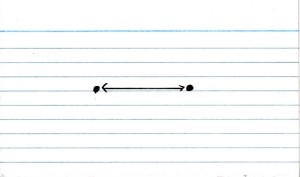

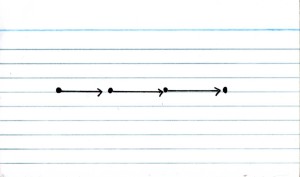

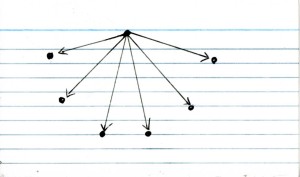

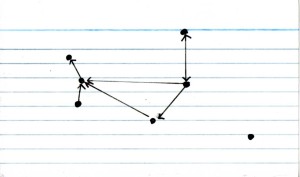

I am interested in the structural conditions for exchange that these sites establish and enable. This could be in the form of dialogue (a two way exchange) 38, order (a flow or chain of directional information) 39, hierarchy (perhaps more akin to the traditional lecture theatre) 40, random or chaotic (like the social interactions in a classroom or social environment) 41, or networked and non-hierarchical (like a round table discussion or the internet). 42

5. ARTISTS 43

Many artists have used the model of a lecture as an art work itself, Fia backstrom and her piece That Social Space Between Speaking and Meaning, is one example. 44 She is also an artist interested in the structures of art education. In her text entitled ‘Kiss my Ass!’ and other Revolutionary Relations in Art Education’ she begins by saying:

‘How about this classic relationship between the student and the teacher? A most intricate dance of power and disavowal set in contradictory motions. From the perspective of the teacher:

– Offering valuable statements, while making sure that no one takes them for truth

– Taking on the role of authority, while harbouring a secret wish to be overthrown

– Secretly encouraging disobedience, while always veiling that desire in covert comments’

And of course, there was Beuys, 45 who in 1974 organised a 10-day lecture tour ‘Energy Plan for the Western Man’ with stops in New York, Chicago, and Minneapolis. Beuys lectured at universities and colleges delivering an ambitious proposal for rethinking the connections between art, science, culture and economics. In many ways Beuys had managed to escape and critique the gallery system, but he still found the time to create a series of multiples, including him substituting his signature black boards for zinc plates, so that he could run off a few lithographs when he got home.

‘the whole question of potential, the possibility that everybody has now to do his own particular kind of art, his own work, for the new social organization. Creativity is national income.’ Joseph Beuys.

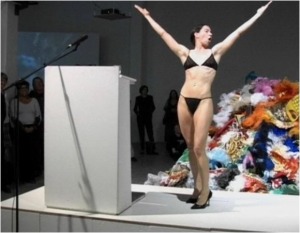

And there are a plethora of contemporary artists undertaking lectures as part of their practice. For example; we have the spectacular showmanship of Mark Leckey (In a Long Tail World 2009) 46; the convoluted and sporadic rambling of Tris Vonna Michell (Auto-Tracking-Auto-Tracking 2009) 47 and the Queen of institutional critique, Andrea Fraser 48, who in the piece ‘Official Welcome’ (2001) hyperbolically adopted various modes of public address whilst taking off her clothes.

Yet, it is her piece ‘Museum Highlights’ (1989) 49, in which she leads an audience around a museum discussing the functional architecture as if it were art works, that I find more interesting. I like the idea of a lecture as a tour, so that there is a parallel between a narrative that runs though time and a subject that runs through space; a lecture without walls.

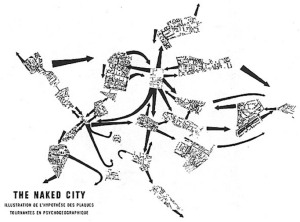

The idea of narrative and space links to the practice of flaneur, and also to the theory of the Derive. 50

The Derive, (literally, ‘drifting’), is a Situationist practice that involves a technique of rapid passage through urban spaces and varied psychological states.

‘There are spaces where experiences coalesce or resonate, so-called ‘unities of atmosphere’, between which red arrows marking trajectories of ‘impassioned attraction’ trace an open narrative. Space is shown to be inhabited, i.e. it is not some contextual container which social relations somehow fill, but a product of the performance of inhabiting. As such, space is incorporated into social practice’

Guy Debord, ‘Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography’, 1955.

This reminds me of a piece by the Egyptian artist, Sherif El-Azma that I saw recently. ‘The Psychogeography of Loose Associations’, is a lecture and a book exploring ideas of phsychogeography and narrative through the potentially fictitious ‘Cairo Psychogeographical Society’. 51

The lecture is available to read online at: http://www.e-flux.com/journal/view/90. Here are a couple of extracts from that lecture:

‘The stalker is a guide, and the job of the guide is to summarize information that might exist in a certain space and time. Guides also centralize and filter history, not only in an attempt to make the traveller a continuation of it, but to comfort the traveller in some way by making him feel that the centre of this megacity is actually a village. 52

Like all other centres, a mythology surrounds this one, a mythology essential for the gravitation of being. Like all other centres, the “vintage” is fetishized, personal histories are redeveloped, sometimes forged, and illusions of historic continuity are mused on.

The centre is an illusion, a spot where wishes come true, so naturally they began to guard it like a treasure; for who knows what wishes a person might have. 53

Thursday October 12, 2007 (8:33 p.m.) 54

Dear W,

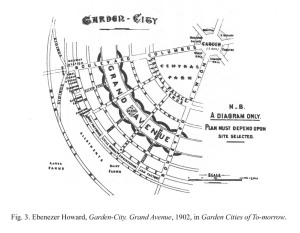

Did u notice the map of garden city? If you take a turn, you end up in the same place. It’s designed as an art deco pattern. Perhaps to keep people in or to protect expats and keep them near the British embassy at that time. From the top, the planning is completely form over function. Can me and you wander it together?’

6. SITE, STRUCTURE, FORM: Analogy and meaning 55

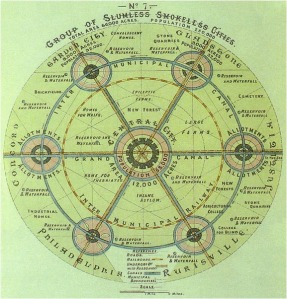

The mention of Garden City takes me to Ebenezer Howard’s 1889 publication ‘To-Morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform’, reprinted in 1902 as ‘Garden Cities of To-morrow’. 56 In this book Howard draws up his plans for the Garden City, a perfect sub-urban environment that could house those relocated from inner city slums and would contain the best elements from both the town (such as opportunity, amusement and high wages) and the country (such as beauty, fresh air and low rents). 57

Although I seem to have moved away from my central focus of the lecture theatre, I still find myself faced with a centralized system. Here the centre is a garden, surrounded by the public amenities of the Hospital, Library, Theatre, Concert Hall, Town Hall, Museum and Gallery.

The central point of the garden reminds me of Foucault text ‘Other Spaces’, 1967:

‘The Heterotopia is capable of juxtaposing in a single real place several places, several sites that are in themselves incompatible. Thus it is that the theatre brings onto the rectangle of the stage, one after the other, a whole series of places that are foreign to one another; thus it is that the cinema is a very odd rectangular room, at the end of which, on a 2 dimensional screen, one sees the projection of a 3 dimensional space, but perhaps the oldest example of these heterotopias that takes the form of contradictory sites is the garden.’

Foucault describes the oriental or Persian garden is a microcosm;

‘The Garden is the smallest parcel of the world and then it is the totality of the world’. 58

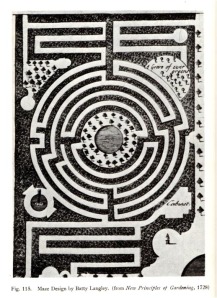

And from the heterotopic and centrally organized site of the garden I move into the maze or labyrinth. 59 What would a lecture be like if it were to adopt this model, with deceptive and irrelevant strands leading a listener away from the centre, finding himself at dead ends, repetitions or loopholes in a narrative?

In a way the labyrinth is the form of the texts of Jorge Luis Borges, whose short stories quite literally mine a library of books to superimpose paradoxical times, places and possibilities. It is also the work of Paul Auster, or Cervantes or the talks of artist Walid Raad. This narrative model moves away from a linear pedagogy of handing pre-determined as relevant information to listeners on a plate and potentially moves towards a more open model of creating meaning. Perhaps in terms that Umberto Eco sets out in ‘The poetics of the Open Work’:

‘In other words, the author offers the interpreter, the performer, the addressee a work to be completed. He does not know the exact fashion in which his work will be concluded but he is aware that once completed the work in question will still be his own. It will not be a different work and at the end of the interpretive dialogue a form which is his form will have been organised, even though it may have been assembled by an outside party in a particular way that he may not have foreseen.’

Or, at the same time, as with any Labyrinth, before one makes it to the centre, there is always a risk of getting completely lost and losing site of both the beginning and the end of your journey. 60

And so I arrive at a site, an architectural or structural form that could be used as an analogy for disseminating information in a public sphere. For me it is both the formal constraints and the heavy heritage of the ‘lecture’ that make it an exciting medium to utilise.

Finally, as a teacher, performer or artist, there is always a decision to be made in terms of what and how ‘information’ is shared, and the kind of communication / power structures you would like to position yourself within. The very act of presenting has meaning by itself. 61